Watermusic II: On transmodal sound, water perfume, and perfumed water

Theories on dissolution, aquatic notes, and perfume's slouch towards liquidity

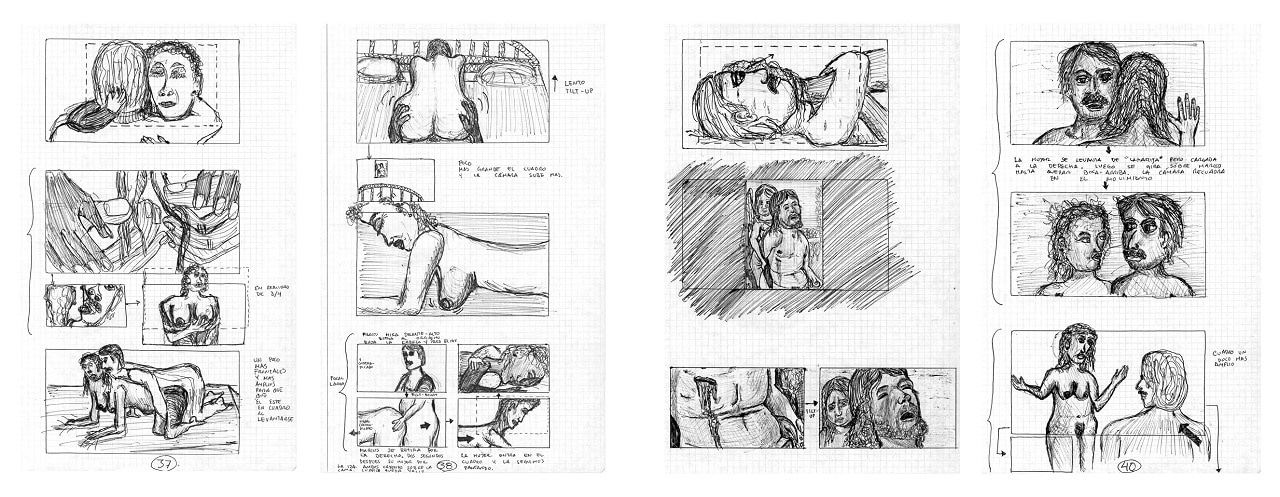

On February 24, 1960 composer, hyper-instrumentalist, and mushroom collector John Cage performed ‘Water Walk’ on "I’ve Got a Secret:" a loosely structured American game show. It is played somewhat for laughs at first, as Cage gingerly proclaims his instruments will include a whistle, a sprinkling can, a rubber duck, and a bathtub. As the performance proceeds, Cage utilizes a number of household objects in unconventional ways, interacting on and around water to produce an assembly of sounds. My wording here is particular, as what Cage does is indeed the slapstick assembly (bringing together) of Schaefferian sound-objects along the axis of recorded time. In his own way, this arrangement is deliberate. Water Walk works from a precomposed visual score: a performative map drawn out in which visual artifacts are designed to be loosely interpolated. Cage is not the only one to have performed this work, and indeed no two performances can or should ever be the same, as both the actions themselves and their outcomes are not wholly predetermined.

In 2019, multidisciplinary artist Christine Sun Kim installed ‘The Sound of Frequencies Attempting to be Heavy’ in the Berlin art space PS120. Relying on a similar boundaryless score notation, Kim works from implied, not actualized performance. Mapping the path of notes arcing downwards, she renders in incredibly large scale scans of colloquially drawn marks, with only a simple instantiation of the title to accompany it. Deaf since birth, Kim’s work does not court vocalization so much as challenge it. Weight, both symbolic and literal, is given to frequency, not sound.

A crucial part of Cage and Kim’s work alike, the dimension of sound which exists as rudimentary vibrational phenomena is privileged here. For Kim, this is done as a means of quantifying the deaf relation to sound, as somatic presence. Cage predates this by holding interest in vibrational sound as a definitive quality of music’s ability to become a ‘sonic event.’ Reverberations against water – hitting, pouring, stirring, slurping – visually mark not only the creation of noise, but trace its resonance across a number of seconds. By interacting with the reverberations of sound waves, the auditory medium is forced to descend from the abstract realm of affect into a simple report of somatic information, unlaid over time. For both Kim and Cage, the result is the same. Sound exists not to herald innate meaning or even innate value, but rather, demarcates a period of time in which a number of psychoacoustic causailities might occur. The sound of a work such as Kim’s Game of Skill 2.0, in which audiences drag a radio that attaches via magnets to an overhead cable to align with it’s frequencies and produce sound, is not as important as the movement they made across both space and time to produce those vibrational artifacts. As Cage writes in his pseudo-manifesto Silence: “a sound accomplishes nothing; without it life would not last out the instant.”

The heart of how vibration is made sacrosanct then, is water. The original tape recorder, it is the first known material structurally malleable enough to respond to resonant changes in frequency. Think of all that water may have borne physical witness to throughout human history: what secrets shared behind garden pools, laughter echoed throughout oceans, gossip exchanged by women washing clothes by the river. In this respect, water seems the perfect subject – at once primordial and modern – to bridge the gap between mediums. I spent this time dwelling on the intermediacy between sound art and visual art in hopes of preparing you for the argument at the center of this work. I believe that just as water proves the most apt means of visualizing the interdependent relationship between performance, sound, and vision, the smell of water notes in perfumery, or all things generally vaporous and aquatic, serves to illustrate the ways in which perfumery as a secondary art form is indebted to its physical nature. When wearing notes that smell liquidy, one becomes distinctly aware of having sprayed liquid upon oneself. Self-evident, perhaps, but so often perfume is described purely as something one smells, rather than a fluid one feels. This smell does not arrive in the nose by way of diffusion or smoke, as was traditionally encountered in rites of incense, but by water. And yet, most perfume is water only in the linguistic sense. A common term used to refer to the high-proof alcohol fragrant oils are suspended in, l’eau is not just a predecessor to toilette, parfum, etc, but refers to the perfume-substance itself. L’eau de L’eau, water of water, is not just an obscure Diptyque release, but a microgenre I consider to be perfumes that smell both ethereal and uniquely reminiscent of their aqueous form. This special type of perfume, by way of smelling exactly how it looks and feels, exists as Bataille once wrote of the animal world: “like water in water.” Spray them, put on some experimental ambient music, and let touch turn to vapor turn to sound turn to smell.

Comme des Garçons’ Odeur 53 is my personal favorite entry in the Odeur series. If nothing else, there is something so poetic to me about the maison releasing some of their most experimental scents in giant blunt force trauma bottles that require you to buy 200ml of perfume just to own the scent at all. It feels to me like a sort of consumer Rorschach test. You’re either stupid enough to buy a half pint of something that smells like printer ink, or you’re cultured enough to see the misunderstood masterpiece behind a perfume with a name that takes two lines of text to list. Beyond provocation, however, I do truly feel that 53 holds its own as a perfume. Launched in 1998, it is the result of a personal commission to the IFF (the laboratory of International Flavour and Fragrance) by Comme’s patron saint, Rei Kawakubo. The labratory itself refers to 53 as “the memory of a smell” – and indeed the copy describing the perfume’s notes is itself a form of concrete poetry worth quoting in its entirety.

Freshness of Oxygen, Flash of Metal, Fire Energy, Washing drying in the wind, Mineral intensity of carbon, Sand Dunes, Nail Polish, Cellulosic smell, Pure air of the high mountains, Ultimate Fusion, Burnt Rubber, and Flaming Rock.

To my nose, the principal accords at play here are wet clay, hot sand, mountain air, and research chemicals. Like an underwater hospital, Odeur 53 smells at once exceedingly simple and strangely complex. Bridging the gap between organic and inorganic, the substance itself is crystal clear – like anointing oneself with holy water from a rocky alien planet. The beauty of this fragrance resides in its subjectivity. I’ve found some of my favorite fragrantica reviews under this heading, as people liken it to crushed flowers, 90s office complexes, and the smell of lighting striking earth. Ozonic, airy, and fresh, wear this anti-perfume to seduce a well-to-do potter by the sea, or to charm the anesthesiologist at your next surgical procedure. Just take a deep breath and count backwards from ten for me, okay dear?

Just as ineffable is multimedia perfumers Folie a Plusieurs’ Post Tenebras Lux. Designed by Secretions sommelier Antoine Lie, this ranks among my favorite of his works, and is perhaps the most subtly affective perfume in recent memory. An aromatic response to a shower orgy scene in Carlos Reygadas’ film of the same name, the three stated notes are “oriental woods, mist, and clean skin accords.” I find PTL wears on the skin like pure vapor itself, smelling like the act of misting water onto skin. This is sensual, but it is certainly not grotesque. If Secretions is naked, Post Tenebras Lux is nude. If I had to pick a single perfume to wear in a sensory deprivation chamber, this would be it. This perfume smells exactly how it looks, clad in minimal hand-painted bottles that serve as art objects onto themselves. When first applied, you smell a saline sort of musk paired with the watery echo of freshly spritzed mistletoe. Into the drydown pine turns to mahogany and pairs with the evaporating sweat of a well-groomed man, holding tightly to skin, yet lasting for hours. In this sense, PTL is the double entendre of skin scents: a perfume that not only wears closely to the skin, but mimics the skin’s unique smell. Wear this to receive gentlemen callers outside of a remote European spa, or to turn off all the lights in your hotel room and watch the entirety of Jeanne Dielman later that night in silence.

J-Scent’s portmanteau Hanamizake (hanami (花見, flower viewing + 酒, sake) is the water perfume’s sheer boozy equivalent. Like drinking underneath bright pink cherry blossoms, the specific fermented rice smell unique to hot sake is produced here with startling accuracy, paired with a bright and fruity accords somewhat synonymous with the actually unscented blossoms of the sakura tree. Part of me almost wishes the fruity-floral aspect of this perfume could be toned down to really spotlight the work done on the more alcohol-forward notes, but I have also found that as it ages, the actual alcohol contained within the perfume itself pairs nicely with its own decaying scent. Another example of l’eau-in-l’eau, one gets the sense that actual cherry-flavored sake, decanted from a bright pink Hello Kitty bottle and sprayed from a plastic atomizer might feel and smell exactly like this. I see potential references to the ambroxan-bomb Kira Kira, inasmuch as shampoo-like fruit is paired with sharply alcoholic undertones. Wear this in Yoyogi Park to take copious selfies underneath the blushing-blossomed trees, or in Shibuya to drink cheap fruity alcohol with your salaryman boss after work until you both can’t see straight.

The last perfume I want to mention is Filigree & Shadow’s NOTGET. Inspired by the Bjork song of the same name, this is the serene freshwater perfume’s foil – smelling like the real ocean, in all its fishy vicissitudes. An impression of genuine ambergris does a lot of work here, adding a fleshy, animalic dimension to a sea water accord formed with ozonic notes and salty musk. One of my favorite parts about this perfume, formulated in water instead of alcohol, is the milky-white texture it shows in bottle and on skin. Of all the perfumes in my collection this one is most easily passed off as an arcane sex potion, all translucent, milky, and wet. Wearing it on skin one gets the sense that you have actually been in the ocean, as the scented water you apply to yourself quite literally looks feels and smells like the spray from a fishing wharf. The only other thing I can think of that smells like this is DS & Durga’s unconventional ode to New York in summer Rockaway Beach. They both seem to evoke not the fantasy of disembodied hands moving through fresh springs, but rather the reality of sweaty human forms in a body of water shared with countless other creatures, human and otherwise. Wear this to twirl around the beaches of Reykjavík, or simply to convince your friends and lovers you moonlight as an underwater exotic dancer for sexually frustrated mermen.

‘eat your lipstick’ is a perfume blog by audrey robinovitz, @foldyrhands

Audrey Robinovitz is a multidisciplinary artist, scholar, and self-professed perfume critic. Her work intersects with the continued traditions of fiber and olfactory arts, post-structural feminism, and media studies. At this very moment, she is most likely either smelling perfume or taking pictures of flowers.

Hello Audrey

I am an instructor of Olfactory Art at SAIC.

If you are EVER in Chicago on a Tuesday our class would love for you to visit!