La Mort en Rose: Myroblysic perfume, Thérèse of Lisieux, and the blessed odor of sanctity

The bodies of saints, ecstatic death, and the ineffabile scent of incorruptibility.

I wrote about perfume and spirituality on this blog for the first time almost exactly a year ago. My concerns then were of scent’s relation to ritual, and the ways in which perfume presents a habit of being to my own life. Needless to say, not only have I lived with the perfumes I wrote about then more profoundly, but I have also made the smell of incense – particularly church incense – into an olfactory fetish of mine almost rivaling this blog’s namesake accord of lipstick. I feel called to revisit some of these fragrances at the dawn of a new era of faithfulness in my own life, and a particular obsession with how scent presents itself in Catholic ritual and theology that I find remains relatively untouched by laity of fragrance-collecting experience.

The divine – like learning, love, and most things worth devoting your mortal body to – is perceived through all senses. It is a concept the Christian tradition can’t get around acknowledging, even in its renunciation. The protestant reformation and subsequent revivalist movements across Anglophone countries sought to reposition the worshipper’s perception of the divine inward – marking the transactional creation and maintenance of the divinity-substance away from the eucharist and within the mind. And yet even the most austere Lutheran cannot escape substantiating their faith. The way in which concrete ritual, repeated song, sight, and smell, forms a material vessel for one’s immaterial spirituality is never evaded, but changed. In this respect, I have found myself extremely interested in how smell not only draws one’s mind to worship, but how by this associative logic, smell becomes itself an aspect of God.

In the conclusion to his transcendentalist trad-larping manual Walden, Henry Thoreau writes: “the volatile truth of our words should continually betray the inadequacy of the residual statement. Their truth is instantly translated; its literal monument alone remains. The words which express our faith and piety are not definite; yet they are significant and fragrant like frankincense to superior natures.” By drawing comparison between the written word and the aroma of frankincense, he touches upon a key aspect of both language and smell. They are not descriptively functional, but semiotically indicative. Words do not flow omnidirectionally to meanings any more than the base of a tree leads directly to its roots. Smell does not so much as describe a feeling or grander notion of God, but like an iceberg, can provide us blind and momentary contact to a vast underworld of mercurial presence. In Gravity and Grace, French mystic and poet-scholar of religiosity Simone Weil writes “two prisoners whose cells adjoin communicate with each other by knocking on the wall. The wall is the thing which separates them but it is also their means of communication. It is the same with us and God.” In this respect words are the wall, and meanings are the prisoners. Smell, a single written word – God the emotinoal resonance of the sentence. All truly evocative art must be like this, and so too must all effective means of worship. Blood calls to blood. “Every separation is a link.”

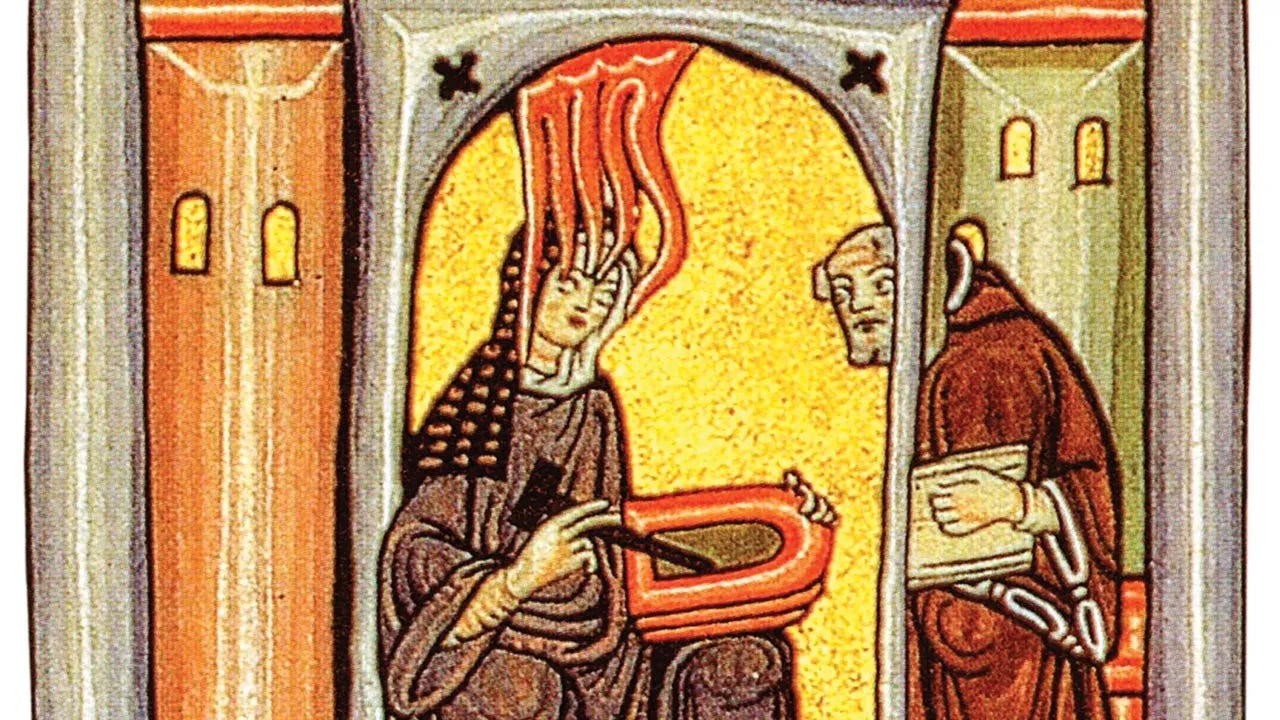

Abbess and insatiable polymath Hildegard von Bingen once wrote “by our nose God displays the wisdom that lies like a fragrant sense of order in all works of art, just as we ought to know through our ability to smell whatever wisdom has to arrange.” There is a fascinating conceit here that smell not only illuminates the good and just, but that the good and just is itself arranged via the structure of fragrance. The ordering of pleasant smells is itself a divine act: God’s will is fragrant because it is just. This reciprocal relationship between beauty and Godliness is commonly presented in secondary religious texts as ecstatic, transcendent, and borderline orgasmic. Herein she speaks not only of perfumed works of art in a capital c Church setting, but a mystic phenomenon that constitutes the pinnacle of how smell, physicality, and the divine intersect within Catholic tradition. I am speaking of the odor of sanctity.

First recorded within oral tradition of the Middle Ages, the odor of sanctity is a smell released at the moment of a saint’s death. Varied in nature but always overwhelmingly pleasant, the presence of this smell serves as proof of this person’s divinity, and often plays a part in convincing the Pope this particular person is worthy of canonization. The smell varies to a degree, but it always follows the internal principle previously asserted that Godly things must smell beautiful, and sinful things noxious. Critic and fellow perfume-obsessive Nuri McBride points out in her brilliant essay ‘The Odour of Sanctity: When the Dead Smell Divine’ – that saints commonly associated with this phenomenon were largely women who lead monastic, disciplined lives of prayer. The implication being that in life they sought to shape their bodies into vessels for the divine, so when discarded in death they bear evidence of the divine having lived within them. The dynamic here is perhaps the most common duality in Christendom, and an equally pervasive way of speaking on and about the bodies of women. The flesh is rotten and impure, the spirit is transcendent and godlike. The actual basis of the Madonna-whore complex, there are and could be countless books written on the ways in which the doctrine of original sin holds women accountable for their mortality above men, but I find it interesting that in this circumstance the odor of sanctity presents an avenue for women’s bodies to be made sacrosanct in decay.

Thérèse of Lisieux is the most notable and interesting case of myroblysia (the expulsion of aromatic liquid, oil, or vapor from the recently deceased bodies of saints) resulting in the creation of nuanced fragrance. Indeed Thérèse, born to devout family in 1870s Normandy, is often called ‘The Little Flower of Jesus’ for her simple philosophy of living in humble devotion to Christ as a single flower among many. Little Flower – the name of Chloe Sevigny’s perfume collaboration with Régime des Fleurs – smells, as Thérèse’s death did, of roses. In her autobiography she writes:

I understand how all the flowers God has created are beautiful, how the splendor of the rose and the whiteness of the lily do not take away the perfume of the violet or the delightful simplicity of the daisy. I understand that if all flowers wanted to be roses, nature would lose her springtime beauty, and the fields would no longer be decked with little wild flowers. So it is in the world of souls, Jesus’ garden. He has created smaller ones and those must be content to be daisies or violets destined to give joy to God’s glances when He looks down at His feet. Perfection consists in doing His will, in being what He wills us to be.

The smell of roses has always been a difficult one for me to parse. At once deemed the ‘king of flowers’ yet derided by many as antiquated, there are as many allegories for rose as there are petals in a flowerbed. Yet I often find the smell of rose absolute in perfumery pales in comparison to the flower itself. There is a certain green, moistened aspect to fresh rose that runs flat and waxy in typical rose soliflores. This is the smell I imagine to have abounded at the moment of Saint Thérèse’s death, in which a scent of roses was reported to have emitted so fragrantly it lingered for months. Jo Malone’s take on the flower, Red Roses, is to me the closest representation of the final moments of Saint Thérèse: its simple refrain of dewy floral pink-ness evoking Thérèse’s promise "after my death, I will let fall a shower of roses.” Wear it to pray her novena, or otherwise to conjure the closest representation of her temperate presence.

Another rose-scented death is that of Saint Teresa of Avila, Carmelite Nun and model for Bernini’s masterpiece, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. An astetic taken to long periods of starvation and self-flagellation, there is a certain irony in her death resulting in such olfactory opulence. Indeed, many of the myroblysiaic saints engaged in frequent and intense mortifications of the flesh. Anorexia mirabilis (the miraculous lack of appetite), was a form of religious anorexia often associated with women and girls seeking communion with the divine. There are even some who theorize that the odor of sanctity is itself a form of ketosis, a natural process that occurs when the body runs out of glucose and begins to metabolize fatty acids. As Ketosis progresses, it volatilises acetone which produces an extremely faint smell, unrecognisable to most. Should this devolve into the pathological metabolic state of Ketoacidosis, customarily brought on by advanced alcohol abuse, starvation, or complications from diabetes, the acetone becomes detectable, even overpowering. Someone engaged in prolonged fasts or dying while in an advanced state of Ketoacidosis would sometimes be reported to emit a strong sweet smell. Scientific explanations aside, there is an undeniable religious resonance to the abnegation of the flesh evoking a pleasant, or Godly smell. In the book Holy Anorexia, Rudolph Bell contextualizes the sanctification of these patterns of behavior in a larger matrix of psychologically analogous behaviors among women, asserting the post-facto justification of disordered eating in the habits of Saints such as Catherine of Sienna is not purely a result of God’s presence, but rather an underlying need to assert a sense of self. As a teenage girl today might mistakenly turn to disordered eating habits to reclaim self-control after traumatic events, so too does the holy anorexic convince the world her behavior is in pursuit of selfless communion God, when in actuality it is a fruitless attempt to be known, if just for a moment, by someone truly and completely. Bell writes – “whether anorexia is holy or nervous depends on the culture in which a young woman strives to gain control of her life.” The development of holy anorexics answers the patriarchal structure of the Catholic Church like the existence of women with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders today mirrors the ruthless standards enforced on women’s bodies. In this sense, the smell of roses, quintessentially feminine flower, rings at the advent of their ascension to Christ like a hollow bell of womanhood’s prison. The process of starvation paradoxically liberates the saint’s from the societal burden of a woman’s body, yet cements her forever fragrant and docile in the annals of time. When self-denial becomes one’s sense of self, masochism’s political and spiritual purpose takes a tragic backseat to the social realities of auto-annihilation. As the sacred texts of Mitski’s old tweets reminds us: “I used to rebel by destroying myself, but realized that’s awfully convenient to the world. For some of us our best revolt is self-preservation.” However one chooses to imagine the starvation and death of Saint Teresa, the ecstatic (from Greek ekstatikos "unstable, inclined to depart from”) beauty with which memorializes the departure of her soul and emits from the remains of her body serves as ephemeral document of the transition from one life to the next.

Other notable odors of sanctity often involve the smell of incense, honey, or a mixture of the two. At the martyrdom of Saint Polycarp, it was recorded that after Roman authorities lit the pyre to burn him at the stake, the air was filled not with the smell of charred flesh, but a beautiful fragrance like that of frankincense. Records describe that “so sweet a fragrance came to us that it was like that of burning incense or some other costly and sweet-smelling gum.” April Aromatics’ Calling all Angels is honeyed frankincense par excellence. Kissing cousin to one of my all-time favorite church incense perfumes – La Liturgie des Heures – Angels trades foresty cypress for sticky-sweet honey and vanillic amber. As a perfume structure, it interestingly claims to have no top notes. Wearing it, one starts in media res – like an epic poem – with an immediate wall of slurred sweet frankincense, sheltering in its smoke a single flowering rose. Drying down into a nondescript blend of opoponax, benzoin, elmi, and amber resin, it clings to skin for hours, and to clothes for days. The demure goddaughter of Hiram Green’s Slowdive and Profumum Roma’s Olibanum, this is church girl eschatological fantasy couture. Wear it to make your neck smell like the last rites of an ancient martyr, or during any other moment you need to call on the fragrant strength of saints.

Perhaps the most unique of the recorded odors of sanctity, Marie d’Oignies, Beguine laity and fervent ascetic, was reported to have emitted a smell of buttery pastries upon her death, despite subsisting on only holy communion near the end of her life. Claiming possession of God-given faculties that made her body reject all food but consecrated wafers, she died a holy anorexic, emaciated and supported by none but her confessor and student of theology Jacques de Vitry. Indeed Vitry possessed a unique and erotic fascination with Marie, later writing her hagiography, and reporting the unique smell of desert bread upon her death. Italian maven of gourmands Hilde Soliani has created her masterwork in Crema di Latte – a perfume that smells of whipping cream and all things indulgently sweet. Primarily photorealistic buttermilk, this lays so dense and creamy on the skin one could practically lick it off. Wear Crema di Latte if the eroticism of denial is not lost upon you, or if the current intersection of consumerism, diet culture, and misogyny that describes certain sweets marketed to women as “naughty” makes you want to take up your desert spoon, pray to Saint Marie of Oignies, and partake in fresh-baked torrid ecstasy for the postlapsarian woman.

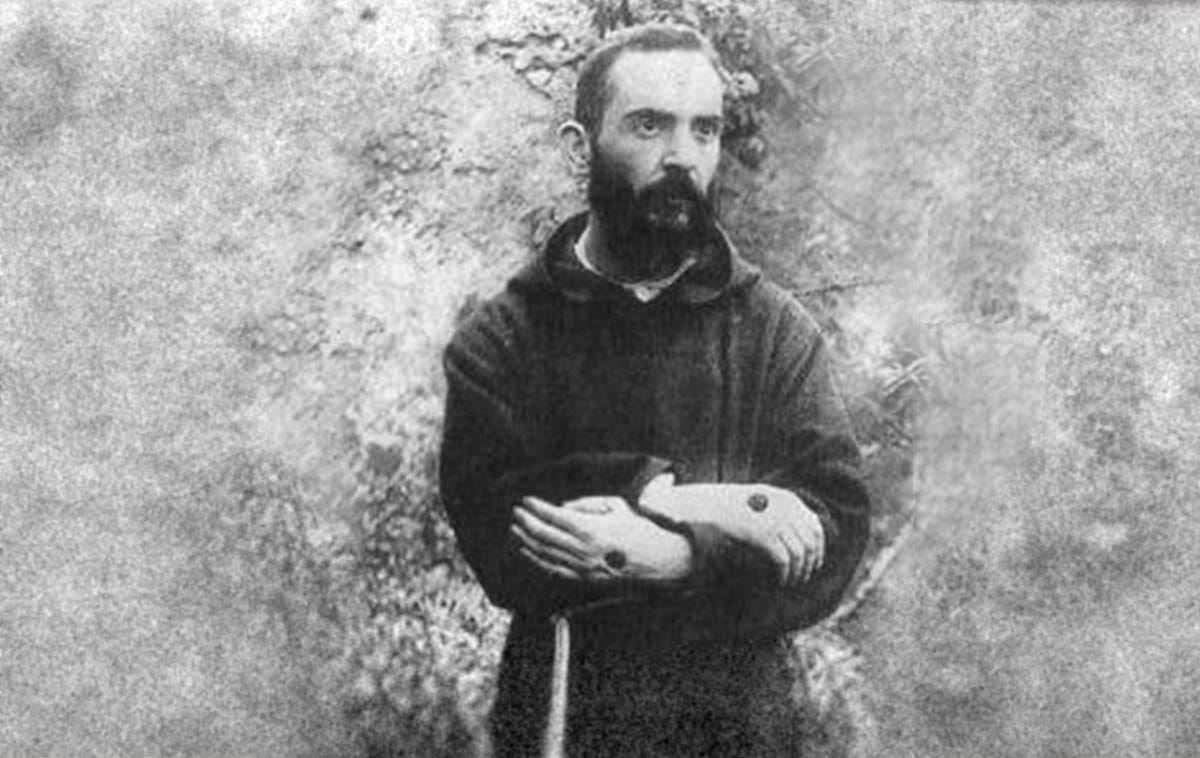

Other minor claims to odors of sanctity are lilies, violets, and in reference to the adored Saint Padre Pio, the smell of smoking tobacco. The latter strikes me as unique due to the tobacco’s lack of association with purity or delicacy. There are frequent records of Padre Pio’s presence while alive producing a powerful floral fragrance, but in death, as if to remember his habits of living, this somewhat contentious and certainly earthly scent of sweet smoking tobacco remains. Easily one of my favorite releases of all time from French heavyweights Diptyque, Volutes in my beloved and sadly discontinued eau de toilette formulation is the smell of women’s makeup powder mixed with Egyptian rolled tobacco cigarettes smoked by well-to-do gentlemen aboard a 1930s ocean liner bound for Saigon – a scent memory plucked from the childhood of founder Yves Coueslant. As an eau de toilette I find the more nuanced faculties of hay, dried fruits, and leathery iris are given space to emerge. The composition on the whole leans a strange sort of leather-honey-tobacco, best compared to the sweet-oriental plumes of Chergui. Wear this perfume to conjure the memory of Padre Pio’s presence – at once mysterious, mystical, and honest.

There is one final intricacy of hagiologic scent I feel worth addressing – which is that in life, the stigmata of certain holy men among the clergy were reported to smell of roses and blood. Indeed Padre Pio is one such stigmatic, but there have been numerous other cases of mirror wounds of Christ emitting a ghastly, fragrant aroma of flowers. Switzerland-based perfumers Tauer have in their creation of Incense Rose, cast the next-best shadow of this particular smell in my eyes. An intense, flaming vision of red roses, its floral scent is crossed with fleshly and pungent castoreum. A secretion from the pheromones of adult beavers, the smell of castoreum is traditionally associated with leathery, intense, masculine fragrances. Here its presence mirrors blood – the Blood – heralded with almost-fizzy clementine in the top notes, and drying down into a highly animalic floral chypre rivaling the likes of Papillon’s Baptist-slaying Salome. Wear Incense Rose to slowly develop miraculous marks of Christ, or simply to take solace alone in the power of His blood.

‘Eat your Lipstick’ is a perfume blog by Audrey Robinovitz, @foldyrhands

Audrey Robinovitz is a multidisciplinary artist, scholar, and self-professed perfume critic. Her work intersects with the continued traditions of fiber and olfactory arts, post-structural feminism, and media studies. At this very moment, she is most likely either smelling perfume or taking pictures of flowers.

i am so fond of teresa of avila <3 it's the church i attend

Surprisingly this is my new interest. I loved the article!